Hello again,

It’s been a while since I’ve written a post here, between full time work, full time study and full time Wife and step-Mum I am finding less and less time for reading.

As you are probably all aware, Christmas is coming!! So while I was trudging around the mall, sliding through tiny gaps between people and trying not make physical contact I suddenly found myself in my safe place, a book store.

Outside the shop people milled about in large throngs saying things like ‘the world is ending’ and ‘Christmas is nigh’ in frightened whispers with wide eyes. I was safely inside the book store where the aisles were wide and unoccupied, people were politely looking at book covers and inside pages, while being aware of the people around them and stepping to one side to let me pass. It was heaven.

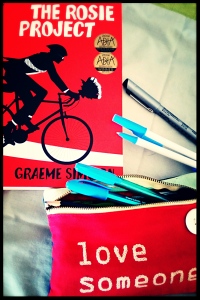

While I was there I picked up a book on a whim, The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion. I recalled that he had been in Canberra early this year promoting his second novel, The Rosie Effect. Since then I had been meaning to buy The Rosie Project, I had picked it up, read the blurb and put it back assigning it to my mental wishlist. So on a moment of Christmas madness I decided to buy myself the book. I took it to the counter where the smiling and polite book shop staff served me as though they hadn’t served 20 000 other people that day. And then, clutching the book to my chest like a life-raft I left the safety of the bookstore.

I opened the book on the journey home, and it took me roughly two days to read because I loved it so much. It is a beautiful, magical journey into the life of Don Tillman.

Despite only having two friends in his life Don is a quirky and very funny character. He excels at a lot things and has an inhuman capacity for learning, but he doesn’t understand people. I can totally relate to Don because I don’t understand people either. There are hints throughout the book that Don may have Aspergers, though it’s never explicitly stated, his actions, lack of emotional understanding, attention to detail, and strictly regimented life lived by schedule fit within the symptoms of being an Asperger sufferer.

I think it’s actually great that Don’s habits are never fully addressed or explained. It means that the story feels more organic, and it leaves the reader with some lingering questions at the end of the novel.

It takes a while before we’re introduced to Rosie, she forces her way into Don’s life against his protests and through a mutual project. We get to see inside Don’s thoughts as he explains his reasoning and tries to understand, and a lot of the time deny his emotions. All while desperately trying to hang on to the order he has established in his life. While on the other hand Rosie is a free spirited, feminist thinking, intelligent woman who finds herself enjoying Don’s company despite his lack of social graces.

What’s really nice is that the plot doesn’t follow a trope. I’m a bit partial to a nice romancy type novel every now and then, but this one was pretty different. Don is not your typical protagonist, and Rosie is not a typical leading lady, but I don’t want to give anything away, so I won’t say any more about the plot.

There is a fair whack of emotion packed in to the novel, I laughed often, I cried at least once, I got angry at sub-characters, and I left the novel feeling, well that would be giving it away. Suffice to say that Don has become one of my most loved characters I’ve read thus far.

In a time that has traditionally as an adult become filled with chaos and Christmas cheer-fear, this novel has been a joyous life buoy to escape to. I would recommend it to anyone who likes comedy and romance all mixed in together, with the added bonus of intelligent characters.

I am getting back to reviewing Time’s top 100, so stick around and I’ll tell you all about Never Let Me Go.

J.M

DearFriends,

DearFriends,